Change is hard ?, why firms fail to scale innovation?

With the acceleration of market and technological shifts and the rise of platform companies, incumbents’ life expectancy has decreased significantly over the years (McKinsey, 2019).

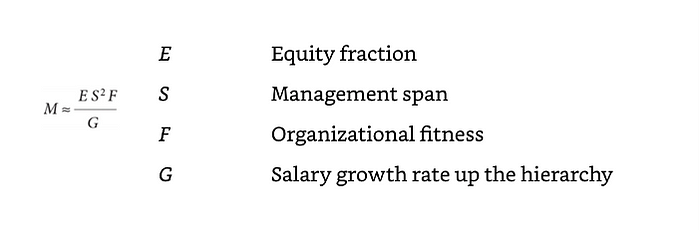

However, platform companies, once disruptive players, have flaws and are subject to much more public scrutiny. Besides, the advent of revolutionary technologies like AI and blockchain gives incumbent players new abilities to be competitive again as cognitive firms, as shown with Microsoft. It requires a massive transformation and a new firm architecture (Iansiti & Lakhani, 2020).

The problem ?

How can non-platform firms change? What do they need to do to leverage the full potential and opportunities AI and Blockchain promised?

The question that raised is how can non-platform firms change? What do they need to do to leverage the full potential and opportunities AI, 4IR, Automation, and Blockchain promised?

There is a high correlation between an organization’s real communication path and software architecture.

Known as the Conway Law, Mel Conway (1968), described “organizations which design systems . . . are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations” (Conway, 1968). It means there is a high correlation between an organization’s real communication path and software architecture. The odds play against incumbent firms. Not many have been able to transform themselves, but it is possible. Like Microsoft recently flipped its strategy since 2014 when the newly appointed CEO, Satya Nadella, “Hit Refresh” (S. Nadella, 2017). The new firm leadership team has embarked on a transformational journey to be an AI, blockchain, cloud-first company, in other words, to be a cognitive firm. Since 2014, the company valuation has grown more than four times from $46 share price in Dec 2014 to more than $200 6 years later [i]. One might legitimately wonder why so few companies succeed in their transformation. Regarding the Conway law, how should companies structure their communication path and structure from a rigid and stable hierarchy to a more fluid, dynamic, and agile leveraging the full potential offer by AI and Blockchain driven architectures?

Change barriers ?

Kurt Lewin (1947a, 1947b), considered the father of organizational change, argues that a change process goes through 3 phases to mainly combat people fear as follow:

1. Unfreeze to get rid of unwanted customs and habits. The author introduces the Force Field Analysis, which analyzes all the factors for and against the change happening.

2. Move/change/transition when the change occurs. The author refers to a role model concept.

3. Freeze when new habits are adopted and institutionalized

While Lewin 3 step transformation process is easy and straightforward to understand, it remains too broad and leaves a high latitude for each step.

Lewin’s change model’s foremost critic focuses on problem solving and fear (Cooperrider & Srivastva, 2013). Appreciated inquiry originating from the Positive Organization Scholarship (Cameron et al., 2003) concentrates on the positive or strength “deviance” side. Appreciated Inquiry is defined as the “cooperative co-evolutionary search for the best in people, their organizations, and the world around them. It involves discovering what gives life to a living system when it is most effective, alive, and constructively capable in economic, ecological, and human terms. It involves the art and practice of asking unconditionally positive questions that strengthen a system’s capacity to apprehend, anticipate, and heighten its potential. The approach interventions focus on the speed of imagination and innovation instead of the negative, critical, and spiraling diagnoses commonly used in organizations (Stavros et al., 2008). Appreciated Inquiry is based on 4-D process:

1. Discovery: questioning and learning what is,

2. Dream: imagining future possibilities,

3. Design: brainstorming and prototyping from insights learned in discovery to achieve the desired state (dream),

4. Destiny: delivering the dream and design by leveraging the strengths and resources lifted during the discovery dialogues.

Kotter (2014) argues in the face of rapid change and mounting complexity, it is essential to have a dual operating system. The first is the traditional hierarchy one. The aim is to run the current business and execute day-to-day tasks. The second is a network system where “ the additional operating system continually assesses the business, the industry, and the organization, and reacts with greater agility, speed, and creativity than the existing one. It complements rather than overburdens the hierarchy, thus freeing the latter to do what it’s optimized to do. It makes enterprises easier to run and accelerates strategic change” (Kotter, 2012). The author observes firms usually go through 3 organizational structures as they grow. First, they start as a network organizing system, then morph into a hybrid network and hierarchy one, and finally a pure hierarchy. At the center of the dual system, there are five principles:

1. A large number of change agents, not the usual few chosen ones. 5 to 10% of the company should be part of the network structure, according to the author.

2. Volunteers with a “want to” and “get to” mindset rather than “have to.” Volunteers bring positive energy and enthusiasm, while appointees might see it as a distraction or, worse, an additional and unnecessary burden.

3. “Head and heart” people, not just “head” because purpose-driven contributors perform better.

4. More “leadership” and less “management.” Dealing with uncertainties, change agents have to be entrepreneurial, agile, and inspired.

5. “Two systems, one organization”, both systems should work hand in hand and not as siloed. Communication between both structures should be smooth and allow the flow of information transiting from one form to another.

For the network structure to work, the author proposes “8 accelerators” as follow:

1. Create a sense of urgency

2. Build and maintain a guide coalition (i.e., groups’ facilitators)

3. Formulate a strategic vision and develop change initiatives designed to capitalize on the ample opportunity

4. Communicate the vision and the strategy to create buy-in and attract a growing volunteer army.

5. Accelerate movement toward the vision and the opportunity by ensuring that the network removes barriers

6. Celebrate visible, significant short-term wins

7. Never let up. Keep learning from experience. Don’t declare victory too soon.

8. Institutionalize strategic changes in the culture

Innovation scale barriers ??

The dual system championed by Kotter is also debated in the innovation management literature. Christensen C. (Christensen et al., 2015; Christensen & Overdorf, 2000) the founders of “disruptive innovation” argue that when an organization sees a disruption coming, they should create and isolate a structure from the core or even considered a spin-off when the new project/venture/product (see figure 1below):

1. It fits poorly with existing values but well with existing processes

2. It fits poorly with your existing processes and values

The authors (Christensen & Overdorf, 2000) define:

- Values as “ the standards by which employees set priorities that enable them to judge whether an order is attractive or unattractive, whether a customer is more important or less important, whether an idea for a new product is appealing or marginal, and so on.

- Process as “ the patterns of interaction, coordination, communication, and decision-making employees use to transform resources into products and services of greater worth.”

Are incumbent firms condemned only to innovate sustainably, as Christensen and Kotter’s research findings suggest? Could they not create and grow disruptive innovation projects/ventures/product in a dual operating system like Xerox PARC and Yahoo Brickhouse innovation lab.

Christensen meets Kotter’s dual operating system when the project/venture/product fits well with existing values but poorly with existing processes. In this case, we are merely talking about “sustainable innovation,” not a disruptive one. By the latter, the authors mean a “process whereby a smaller company with fewer resources can successfully challenge established incumbent businesses. Specifically, as incumbents focus on improving their products and services for their most demanding (and usually most profitable) customers, they exceed the needs of some segments and ignore the needs of others.” AI and blockchain fall in this category for the most part (i.e., autonomous vehicles, personal assistants in AI or smart contracts, etc. in the blockchain). Are incumbent firms condemned only to innovate sustainably, as Christensen and Kotter’s research findings suggest? Could they not create and grow disruptive innovation projects/ventures/product in a dual operating system like Xerox PARC and Yahoo Brickhouse innovation lab.

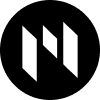

Some argue that it is possible. However, it requires a different approach, mindset, process, leadership, and skillset, as shown at GE (Immelt et al., 2017) and Apple (Podolny & Hansen, 2020). On leadership, Alex Osterwalder (Osterwalder, 2015) advocates for the appointment of a “Chief Entrepreneur” who is responsible for innovation while the CEO runs the existing business. Tushman and colleagues (Smith & Binns, 2011) recommend appointing an “Ambidextrous CEO” who excels at both searchings (discover and grow new opportunities) and executing (run the day to day business efficiently with scale). Eric Ries, the father of lean startup (Ries, 2011), and Steve Blank (Blank, 2013) advocate for an entrepreneurial mindset, agile and experimental process-driven new project/venture/product development approach. More recently, Safi Bahcall (2019), a researcher and entrepreneur, citing examples from DARPA, Amazon Lab 126, Amgen, Lucas Film, Apple, and many others, explains that the main risk in a dual operating system is the “phase transition” when the project/venture/product jumps from one system to another. He argues when group size exceeds a specific number; incentives shift from encouraging a focus on “loonshots” (aka innovative project) to promoting a focus on careers (the politics of promotion). Adjusting the structure can restore the focus on loonshots. He proposes an equation to find the group size number equilibrium as follow in figure 2:

Since the equity fraction E is in the numerator, as E increases, the magic number M gets larger. That means an increasingly larger group of people can work together, free of politics, in the loonshot phase. It means people spent time on projects rather than on politics. The management span S is also in the numerator (at double power). Increasing management span reduces the number of layers, which reduces the importance of politics. It also raises an employee’s stake in project outcomes. Both of which favor focusing on loonshots rather than career interests.

In a dual operating system (searching vs. exploit), Tendayi Viki, Toma, Dan, and E. Gons (2019) argue that large companies need to adopt an innovation ecosystem that encourages corporate-startup creation. They define the latter as “the creation of new products and services that deliver value to customers, in a manner that is supported by a sustainable and profitable business model.” The authors propose five factors to support the innovation ecosystem as follow:

1. Enabling function: support the innovation or network teams get from the companies’ functions like HR, Legal, Finance, etc.

2. Tools and resources: the usual tools companies used are not suited for corporate startups. For example, move from business case to business modeling, traditional accounting to innovation accounting, financial accounting to lean analytics, etc.

3. Innovation catalyst: firms need to provide training, mentoring, and coaching to the innovation network teams. For example, Intuit was able to scale their D4-D (Design to Delight) innovation programs by training many people acting as ambassadors/coaches/evangelist from all over the world. Those coaches then helped local teams.

4. A community of practice: Innovation or network teams need the support of an engaged community of practitioners that interact regularly. This community, or “guiding coalition” as Kotter (2012) described shares and exchange best practices, knowledge, and tools.

5. External partnership: to keep up with the world market and technological changes, innovation, or network teams must keep updated on global best practices and be open to working with external partners. Open innovation (Dahlander & Wallin, 2020) collaboration can be a powerful vehicle.

Depending on the maturity of the company, they define 12 steps to follow to implement a thriving innovation ecosystem to maximize corporate-startup success:

1. Explore your context. Audit the company’s strengths and weaknesses, environment, past successes, and failures to frame the starting point.

2. Get executive buy-in from C-level and board members.

3. Develop an innovation thesis that is the “strategic vision” (Kotter, 2012) the innovation network team will pursue. It is the equivalent of venture capital investment thesis that is the direction and guiding principles they follow when selecting a project to another.

4. Map your portfolio. The firm should have a balanced portfolio of project/venture/products in terms of horizons (core, adjacent, transformative) but also in terms of product life cycle or growth stages (create, growth, mature, decline, renew)

5. Choose one or a combination of innovation models from open innovation, accelerators, innovation labs, etc. The idea here is, to begin with, the best-suited innovation model based on company maturity and capabilities.

6. Create an innovation framework. There are other powerful frameworks such as Ash Maurya’s Running Lean (Mauray, 2012) and Steve Blank’s Customer Development Process (Blank, 2013). V. Tendayi (2019) argues that it is more useful if a company develops its bespoke framework. For example, Intuit has its D4-D framework. Adobe has the Kickbox, and Pearson has the Lean Product Lifecycle. The company’s own built framework is based on its context, specific innovation challenges, strategic goals, and the chosen innovation model.

7. Work with enabling functions. They can help the innovation team in their activities. For example, the legal support team can support patent applications, contract terms negotiation, privacy, and IP protection.

8. Create tools and platforms for innovation or network teams.

9. Develop innovation capabilities through training, mentoring, and coaching. For example, at Adobe, employees must attend workshops before embarking on innovation or network projects[ii].

10. Set up investment boards, similar to “executive committees” (Kotter, 2012) or investment boards for venture capital firms that will help, support, mentor, and guide the innovation or network team. They do not decide upon something; however, their role is seen more as alert advisors.

11. Choose key metrics to speak the same language between the innovation network teams, the executive committees, and other stakeholders. Those metrics are not based on traditional business case standards instead on innovation accounting defined as “evaluating progress when all the metrics typically used in an established company (revenue, customers, ROI, market share) are effectively zero” (Ries, 2017).

12. Build the community space for innovation or network teams to share ideas, discuss best practices, and learn from each other projects.

Little research covers those challenges either in the platform related literature(Rietveld & Schilling, 2020) and change management (Kotter, 2012) alone. Our research’s originality is the multidisciplinary approach from change, innovation, technology, and platform management theories, literature, and best practices in light of the cognitive firm’s advent.

References

[i] Source: Google Finance, data from 13th dec 2020, https://www.google.com/finance

[ii] Source : Forbes, 2015, https://www.forbes.com/sites/mzhang/2015/08/19/adobe-kickbox-gives-employees-1000-credit-cards-and-freedom-to-pursue-ideas/?sh=5053cd194b0f

Christensen, C. M., & Overdorf, M. (2000). Meeting the challenge of disruptive change. Harvard Business Review, 78(2).

Christensen, C. M., Raynor, M. E., Rory, M., & McDonald, R. (2015). What is disruptive innovation? Harvard Business Review, 93(12), 44–53. https://hbr.org/2015/12/what-is-disruptive-innovation

Conway, M. E. (1968). How do committees invent. Datamation, 14(4), 28–31.

Iansiti, M., & Lakhani, K. R. (2020). Competing in the Age of AI: How machine intelligence changes the rules of business. Harvard Business Review, 98(1), 60–67.

Immelt, J. R., Ranjay Gulati, & Steven Prokesch. (2017). How I Remade GE and What I Learned Along. Harvard Business Review, September-October. https://hbr.org/2017/09/inside-ges-transformation#how-i-remade-ge

Kotter, J. P. (2012). Accelerate! In Physics World (Vol. 32, Issue 10, p. 29). https://doi.org/10.1088/2058-7058/32/10/25/pdf

Osterwalder, A. (2015). The C-Suite Needs a Chief Entrepreneur. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2015/06/the-c-suite-needs-a-chief-entrepreneur

Podolny, J. M., & Hansen, M. T. (2020). How Apple Is Organized for Innovation: It’s about experts leading experts. Harvard Business Review, November-December, 86–95.

Rietveld, J., & Schilling, M. A. (2020). Platform Competition: A Systematic and Interdisciplinary Review of the Literature. SSRN Electronic Journal, 44(0), 0–56. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3706452

Smith, W. K., & Binns, A. (2011). CEO Ambidextrous CEO. Harvard Business Review, June.

Bahcall, S. (2019) Loonshots. St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

Blank S. (2013). The Four Steps to the Epiphany. K&S Ranch.

Choudary S.P.; Van Alstyne M.W.; Parker G.G. (2017). Platform Revolution: How Networked Markets Are Transforming the Economy and How to Make Them Work for You. W. W. Norton & Company.

Kotter J.P. (2014). Accelerate Building Strategic Agility for a Faster-Moving World. Harvard Business Review Press; 1st edition

Maury A. (2012). Running Lean: Iterate from Plan A to a Plan That Works. Lean O’Reilly; 2nd edition

Nadella S.; Shaw G.; Nichols J.T. (2017). Hit Refresh. HarperBusiness.

Ries, E (2017). The Startup Way. Penguin Books Ltd.

Viki T.; Toma D.; Gons E. (2017). The Corporate Startup: How established companies can develop successful innovation ecosystems. Vakmedianet.

Most Popular

Digital transformation, Innovation

New Web3 and Blockchain Advisory Service

Proud to announce new blockchain consulting and advisory services with a team of …

Digital transformation

Change is hard ?, why firms fail to scale innovation?

With the acceleration of market and technological shifts and the rise of platform …

Innovation

The Cognitive firm = AI + Blockchain

The Cognitive firm = AI + Blockchain Recently, the rise of artificial intelligence …

Digital transformation, Innovation, Product Management

Why product development projects are slow?

The WTF project mgt and team collaboration problem Today, complex products = complex …

Design & Product, Innovation

WTF is IoT °_°, how big is it and why now?

The definition There is a lot of hype on IoT recently but what …

Uncategorized

RGPD

POLITIQUE DE PROTECTION DES DONNÉES ARTICLE 1. OBJET DE LA POLITIQUE DE PROTECTION …